ACE’s Center for Policy Research and Strategy (CPRS) today released its second issue brief in a three-part series on Minority-Serving Institutions (MSIs), “Tribal College and University Funding: Tribal Sovereignty at the Intersection of Federal, State, and Local Funding.”

(1 MB PDF)

CPRS invited scholars to analyze Delta Cost Project Data and other relevant data sources to explore the financial profiles of Hispanic-Serving Institutions (1 MB PDF), Tribal Colleges and Universities (1 MB PDF) and Historically Black Colleges and Universities and consider the financial sustainability of these vital institutions.

Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs) provide many Native and

non-Native students with access to a postsecondary education and

contribute directly to tribal and national goals of improving

educational equity and economic capacity. The United States’ 37 TCUs

enroll nearly 28,000 full- and part-time students annually. TCUs, which

primarily serve rural communities without access to mainstream

postsecondary institutions, have seen a growth in enrollment over the

last decade, increasing nearly 9 percent between academic years 2002–03

and 2012–13.

Although the Native population in the United States has increased 39

percent from 2000 to 2010, Native student enrollment remains static,

representing just 1 percent of total postsecondary enrollment. Despite

the need and growing population, American Indians and Alaska Natives do

not access higher education at the same rate as their non-Native peers.

The authors of the brief found that TCUs face inequities in federal,

state and local funding that limit the institutions’ ability to further

their impact on the tribal communities they are chartered to serve.

Five takeaways from the brief include:

- TCUs are funded through the federal Tribally Controlled Colleges

and Universities Assistance Act of 1978, and despite increases in both

authorization and allocation, federal funding has not kept up with the

steady growth of the Native population at TCUs.

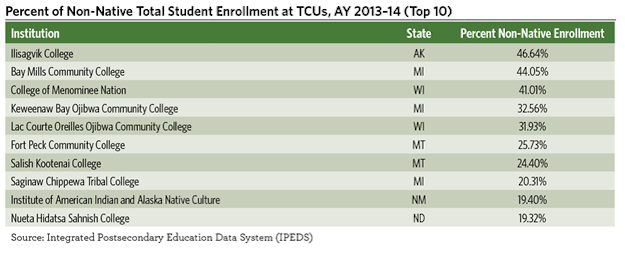

- Unlike other public minority-serving institutions, state and local

governments have no obligation to appropriate funding to TCUs, and the

majority of states do not provide any financial support to TCUs even as

these institutions enroll significant numbers of non-Native state

residents.

- TCUs are limited in their ability to increase tuition to fill

revenue gaps because the majority of their students live in poverty and

cannot afford to pay higher tuition costs and are less likely to take

out student loans.

- The chronic underfunding of TCUs may jeopardize the educational

attainment of indigenous students, exacerbating attainment gaps that

exist between Native and non-Native populations.

- The formula for federal funds only allocates money for Native

students. TCUs receive zero federal funding for non-Native students, and

on average, 16 percent of the student population at TCUs is non-Native.

(See the chart below.)

As

the Native population continues to grow, so will the need for TCUs to

provide access to quality postsecondary training and credentials, which

will necessitate increased funding, the authors conclude.